Media management strategies to help you maintain well-being amid a flood of violence on social media

Key points

- Social media is flooded with violence and carnage from the Hamas-Israel war.

- TikTok is a go-to source for world events putting users at risk for emotional distress and misinformation.

- Violent images trigger fight or flight, decrease cognitive scrutiny, and increase persuasive impact.

- Using media management strategies can protect your mental health.

It’s hard to escape the horrors of the Hamas-Israel war when violent and gruesome images flood the media. Conflicting reports make staying current difficult, increasing our sense of “need to know”—leading quickly to doomscrolling behaviors like we saw during COVID-19. The tendency to look and keep looking is normal–an instinctive reaction and part of our survival mechanism. That doesn’t mean it’s good for you. How do you stay current without damaging your mental health?

From TV to TikTok: Changes in Information Flows

Vietnam was the first TV war. However, with only three major broadcast networks, access to information was limited. Keeping up meant nightly news coverage. Those days are long gone. Social media is the main source of news for over half of Americans.

TikTok and Instagram videos on the Israel-Hamas conflict have drawn billions of views. They are gruesome and frightening illustrations of the violence of war. Not all of them are real, but they are visual. Images deliver much more information much faster than any other type of data. Images are processed 60,000 times faster than text, requiring no cognitive. Videos have spatial and personal context, further amplifying emotional reactions embedded in memory due to the impact on the amygdala, or the emotion center of the brain (Ewbank et al., 2009).

Emotions Lead to Mindless Sharing

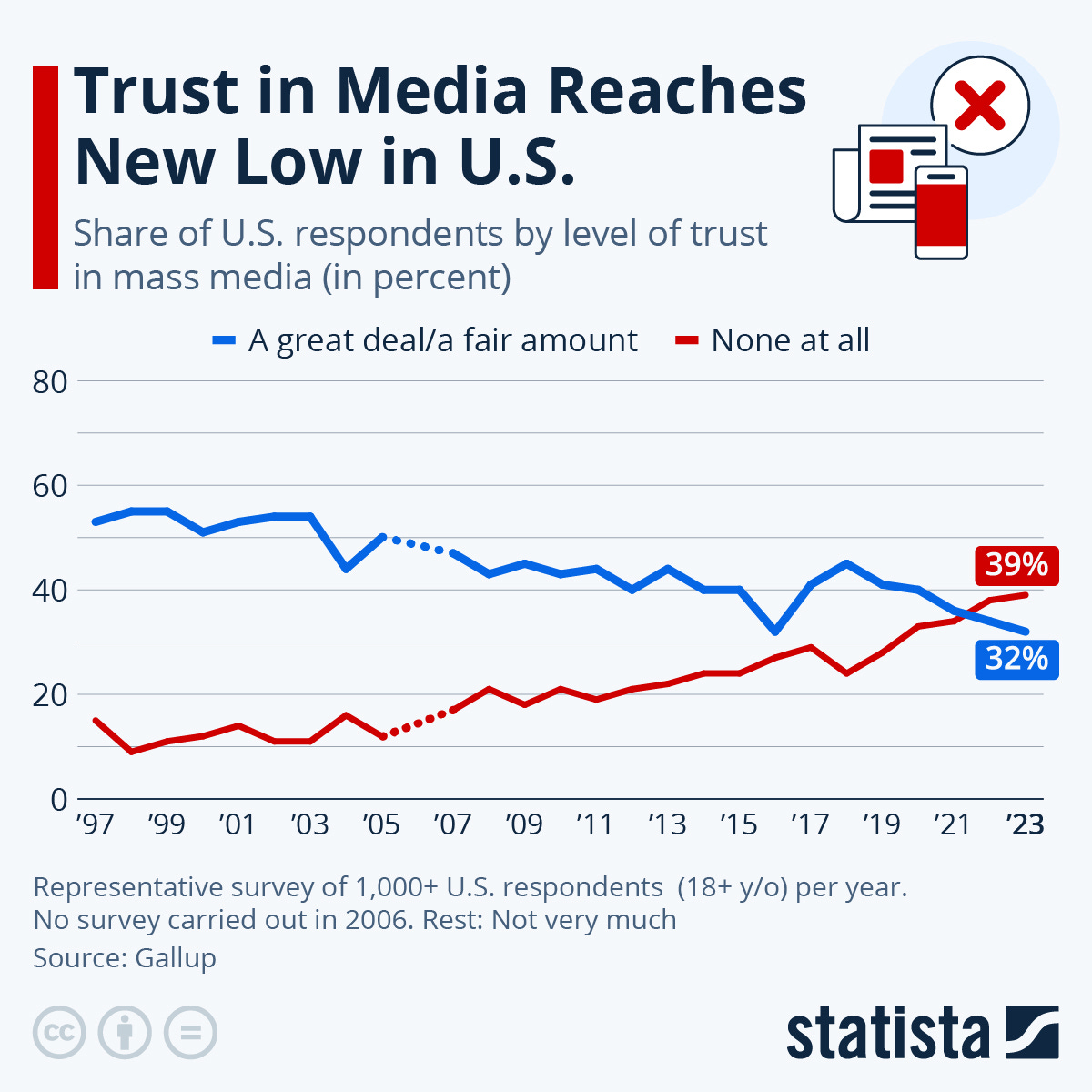

There has always been misinformation in the media. The sheer volume of disinformation was strategic, orchestrated to create fear and confusion, taking advantage of American’s falling trust in media, which has plummeted (Associated Press, 2023). The decrease in trust drives people to social media, where emotion is the main currency for attention. Emotional reactions, whether horror, compassion, or outrage, reduce cognitive scrutiny and counter-arguing and increase reactive and impulsive behaviors. The result is the mindless sharing of inaccurate and misleading content without taking the time to question or confirm.

Stressful Media Creates a Downward Emotional Spiral

Whether true or not, viewing graphic and violent images can be extremely stress-inducing, increasing uncertainty and fear. A steady diet of negative news can increase the risk of anxiety and depression and, as George Gerbner pointed out, make the world seem more dangerous (Gerbner & Gross, 1976).

Our brains instinctively pay attention to any potentially dangerous situation to keep us safe as part of our survival mechanism. The brain’s inability to reliably distinguish between virtual images and real physical threats amplifies the fight or flight response.

Even the sheer volume of available information can create information FOMO, the sense that we are missing something critical to our well-being. This creates a self-reinforcing downward emotional spiral. Consuming violent and gruesome content creates a scary environment and causes anxiety. Anxiety triggers the need to know to make us feel more in control. The need to know sets off the urge to search and scan, which results in more violent content, and so on and so on. The more stressed we become, the more we search, the worse we feel, and the more vulnerable we are to anyone who offers up “answers” so the world makes sense again, like conspiracy theorists, compelling TikTokers, and other misinformers.

Ease Your News Anxiety with 7 Media Management Strategies

Self-awareness is the key to dealing with distressful media content (and maybe life, too).

- Pay attention to make sure your news consumption is giving you something new, and you’re not just ruminating and rereading. This is engaging in the online equivalent of rubber-necking.

- Monitor the emotional impact of scrolling and be aware of your emotional limits before, during, and after reading about conflict or watching videos. If it’s really getting to you, keep a journal so you can identify patterns.

- Taking a news break—even a short one—can help reset your brain, helping you to be more critical and less emotional when you evaluate what you’re seeing.

- Evaluating your priorities creates perspective in case your news obsession is putting a dent in your productivity or general functioning.

- Violent and negative content can affect not just you but those around you. No one wants to hang out with someone who is perpetually angry, raving, or unpleasant.

- Avoid the misinformation trap by analyzing, triangulating, and validating information before you get emotionally carried away and start sharing.

- If you’re going to read the news, do yourself a favor and front-load some silly cat videos or cooking demos to provide a positive emotional buffer.

Learning to manage media behaviors lets you monitor the news so that you feel well-informed and helps you avoid many of the paralyzing emotions that, in fact, make you less effective for the rest of your life. Anger and fear or feeling out of control diminish your ability to feel empathy for others and hamper your compassion, understanding, and ability to listen to different points of view. These are qualities we need all the time, but especially during times of crisis.

Up next: 7 Strategies to Help Your Kids Cope with War Images on Social Media

References

Associated Press. (2023, October 24). Ap fact check: Misinformation about the Israel-Hamas war is flooding social media. Here are the facts. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/israel-hamas-gaza-misinformation-fact-check-e58f9ab8696309305c3ea2bfb269258e

Ewbank, M. P., Barnard, P. J., Croucher, C. J., Ramponi, C., & Calder, A. J. (2009). The amygdala response to images with impact. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 4(2), 127-133. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsn048

Gerbner, G., & Gross, L. (1976). Living with television: The violence profile. Journal of Communication, 26(76).

Dr. Pamela Rutledge is available to reporters for comments on the psychological and social impact of media and technology on individuals, society, organizations and brands.

Dr. Pamela Rutledge is available to reporters for comments on the psychological and social impact of media and technology on individuals, society, organizations and brands.