Celebrities dominated on and off the field at Super Bowl LVIII but psychology explains how emotion and meaning-making deliver engagement in commercials.

As a media psychologist, I am interested in the Super Bowl as a cultural phenomenon and in the psychology of Super Bowl ad content and how media coverage reflects popular culture and connects with audiences. This year, thanks to Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce, some of the cultural underpinnings of the Super Bowl were exposed as hardcore NFL fans resisted the Swifties tsunami. Fandoms are tribes, defined by shared identities and rituals that signal allegiance. It’s hard to think of two more committed fandoms than the NFL and Swifties. If the Swifties stick around, what rituals will merge? This may be the first time a Super Bowl had friendship bracelets and a relatively tame, family-friendly line-up of commercials. What do you think?

In this post, I break down two popular Super Bowl commercials, CeraVe and Dove, looking at the importance of cognitive contexts like mental models and the impact of visual processing. While I’m talking about media here, the principles apply to every type of human communication and the cultural context of media content can be very illuminating from the perspective of teens.

Thanks for reading!

Key Points

- Competition for “best” commercial is as fierce as what happens on the field.

- It was a big year for the use of celebrity endorsements as marketers tried to break through the noise.

- A mismatched celebrity-brand collaboration risks the vampire effect—where the celebrity overshadows the brand.

- Popularity doesn’t mean a commercial is successful in driving purchase intention.

- Audience heuristics, mental models, and expectations will determine how an audience interprets a marketing message and its ultimate effectiveness.

- Visual content that conflicts with the brand message creates cognitive dissonance and undermines the intended impact.

Nielson reported that Super Bowl LVIII had 120.3 million viewers, putting it second on the list of most-viewed American television events behind the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing. Emotions ran high with the excitement over a halftime show by Usher et al., the possibility of Taylor Swift sightings, and a game that kept viewers on the edge of their seats until the last minute of overtime. It was a dream come true for advertisers and their highly-anticipated Super Bowl commercials. They couldn’t have asked for a more riveted audience for their $7 million per 30 seconds of airtime.

Intense emotional expectations of pleasure and pain are powerful motivators of attention and recall. Both positive and negative emotions activate brain mechanisms that ensure our basic survival. They also enhance deep thinking about the things we care about, increasing effortful processing and longer-term retrieval (Immordino-Yang, 2016). The stage was set for impact, and the experts have selected their favorites, but does a commercial’s popularity ensure effectiveness for a brand?

A popular Super Bowl commercial gets a lot of mileage beyond the game broadcast minutes. The Internet is full of “best and worst” lists as journalists, marketing experts, and bloggers gave the commercials extra exposure by sharing them to illustrate their analyses. In a coup for CeraVe, Dunkin’ Donuts, and Verizon, the TODAY show replayed all three. Celebrities like Michael Cera, Ben Affleck, Jennifer Lopez, Matt Damon, Tom Brady, Beyonce, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Danny DeVito, and Christopher Walken were notable standouts—amplified by so many replays.

Star power is a reliable mechanism to get attention because it activates brain regions involved in making positive associations, building trust, and encoding memories. Instant recognition, which is increased by exposure, facilitates an emotional tie, and the ‘liking’ of a celebrity is assumed to have a halo effect, enhancing the brand (Moraes et al., 2019). The reliance on celebrities without considering brand/target audience alignment can also backfire, leading to the dreaded vampire effect, where content and celebrity overshadow the brand (Erfgen et al., 2015).

Competing Against Hype and Expectations for the Super Bowl Win

Super Bowl hype works both ways. Expectations are a bitch anyway, but high expectations are the worst. They leave a lot of room below the bar and very little space above. Everyone knows advertising in the Super Bowl is a big deal and all that meaning becomes part of the message, framing expectations and unleashing relentless pre-game speculation and post-game analysis. Under the Super Bowl spotlight, the misses are more noticeable because the bar is higher. While some say that there is no such thing as bad publicity, ending up on the “worst” list is unlikely to make an advertiser’s day especially if it calls a brand’s authenticity or values into question. Although–good news, bad news–it does result in increased exposure since every “best” list is incomplete without the “worst.”

Popular, memorable, and actionable are not equivalents in marketing. In a mad scramble for attention to justify a Super Bowl investment, many Super Bowl LVIII commercials leaned heavily into sizzle at the cost of communicating a brand’s purpose and value. Consumer purchase behaviors are motivated by more than being entertained or even awareness. (Read more about the importance of brand-value alignment in Cynthia Lieberman’s article “Medium is the Message: How Super Bowl Ads Boost Affinity“.)

Emotional response and social influence are powerful contributors to brand awareness and purchase intentions. Social influence describes how we intentionally and unintentionally adjust our behavior to fit in with our social worlds. Social influence can take many forms, from wanting to “be like Mike,” (conformity, aspiration, and identification) and wanting to be part of a group (peer pressure, obedience, and affiliation) to accepting another’s authority and leadership. Approximately 20% of viewers were rooting for the Chiefs because of Taylor Swift, Adele included.

Social influence increases the desirability of group-promoted behaviors and accelerates consumer decision-making. In popular culture, celebrity status confers authority beyond a known area of expertise, even for paid endorsements. The status conferred by celebrity builds consumer confidence. If the celebrity-brand choice is right for the target audience, then the celebrity resonates and their appeal creates a halo effect feelings of trust and safety for the brand. Our reliance on celebrities to inform our decision-making may sound shallow, but, as evolutionary psychologists have noted, humans are not alone in being star-struck. Primates also follow the lead of high-status group members in their group (Kuchta, 2021).

Does the Commercial Reach the Right Audience?

Advertisers create the commercials, but the audience gives them meaning. Audience members interpret all information, including media content, influenced by subconscious instinctive responses and heuristics, and conscious mental models. These filter and evaluate media content to help the brain decide if it’s worth allocating its scarce attention resources to convert sensory input into some form of meaning. An individual’s information processing system determines if and how a commercial has value—whether it’s entertaining, emotionally rewarding, or persuasive.

When advertisers understand the audience’s beliefs, mental models, and self-narratives, the intended message is likely to hit the spot. However, the best, most clever ads can entertain without delivering a clear message. How many times have you laughed at a commercial, but later had no idea what they were advertising?

Here are two examples of “best commercials” looking at CeraVe and how cognition constructs meaning from context and Dove and how visual information influences interpretation.

CeraVe: The Importance of Cognitive Context

The CeraVe campaign got high marks from almost everyone. It relied heavily, however, on pop cultural context. For example: there were pre-Super Bowl transmedia extensions like Michael Cera handing out autographed CeraVe samples, there were Reddit threads a couple of years ago asking “Is Michael Cera connected to CeraVe?”, and there were more than 450 Influencers that were hired to fuel speculation about the Cera/CeraVe connection. If you had never watched Arrested Development or Barbie (among many other things) and didn’t immediately recognize Michael Cera, the campy, tongue-in-cheek commercial might be entertaining, but you’re likely to miss what about Michael Cera makes it funny. Without cultural context, interpreting content—especially visuals—is cognitively labor intensive. It can interfere with brand recognition while you’re trying to figure out what’s going on.

The positive response on social suggests that CeraVe’s target audience had the necessary frame of reference to enjoy the commercial and “get” the satirical and somewhat irreverent commercial. But good news for CeraVe: With all the attention, even those culturally challenged individuals who missed all the references are probably curious enough to check out CeraVe. So while they may not have the cultural context, they now have social proof of the cultural value

Dove: The Meaning-Making Power of Image

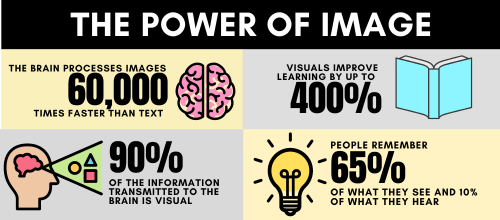

In a 30-second spot, the visual content has to align clearly with the brand message. Images are not only processed more quickly than language, but they also contain much more information. Consider the following: the brain processes images 60,000 faster than text (Vogel et al., 2005); 90% of the information transmitted to the brain is visual (Mehrabian, 2017); visuals improve learning by up to 400%, and visual memory has far greater recall than auditory, with people remembering 65% of what they see compared to 10% of what they hear (Dale, 1969).

The brain organizes new information into a narrative to construct meaning (Herman, 2013), but all new information is processed in the context of stored information. Therefore, visual information unconsciously frames the accompanying verbal messages before it’s even translated from symbols into meaning and then contextualized. Visuals facilitate learning by providing a framework, but, only if the message and visuals align. If the verbal message is not consistent with the visuals, the message may be misunderstood or ignored in favor of the image. Pharma company commercials with text showing the list of side effects superimposed over emotionally warm and fuzzy images are a good example of this. (See also the brief post “Imagination Influences Visual Perception” on how what we think (our imagination) influences what we “see.”

Because of the stickiness of visual images, I worried about the Dove commercial. I’m a big fan of the amazing job Dove has done in their commitment to promoting positive body image for girls and women and have written about them before. (See Can Selfies Redefine Beauty? Dove Thinks So and Dove Continues to Push the Limits of Cause Marketing with a “No Digital Distortion” Label”) So, like many, I expect Dove’s messaging to emphasize the societal disconnect between the triggers of negative body image that undermine self-confidence and the need for healthier self-esteem. In the Super Bowl commercial, the video shows a series of girls having sports “fails.” The background song “It’s a Hard Knock Life,” also highlights difficulties. So we feel them too. The brain has mirror neurons that automatically replicate the neural communication of observed behaviors. This includes physical movement as well as emotional experience inherent in the observed action. In this case, we probably all remember episodes of pain, embarrassment, frustration, and failure that are unpleasant but necessary for the development of expertise. Getting back up and trying again requires resilience and persistence. I expected to see that part, too.

Neuroscience has shown that negative emotions in the place of an expected reward activate the part of the brain that depresses the neural reward system, contributing to a more pessimistic Eeyore-esque outlook, on the lookout for further misfortune. While this may have some evolutionary benefit, it doesn’t help here. In the context of Dove, I assume the sequence is meant to show the challenges girls face and the uncertainty over self-worth. However, the series of falls, slips, and flops during sporting events combine to create an image of girls as not competent and it does so without making an emotionally salient image of the desired outcome—interventions to keep girls in sports. Images are critical to message transfer. Without giving the viewer’s brain an image of the positive goal or moment of transformation, as Dove has done so many times, the viewer is less likely to be inspired and empowered to invest in the activities and support needed to build girls’ self-confidence and self-esteem. I know what Dove is up to, so can translate what I saw into what I assume they meant. For people not already on board, they need some idea of what they can do to help achieve that.

Psychology Can Make Winners in Commercials and Life

Super Bowl commercials get a lot of pre-game build-ups and then face scrutiny for their entertainment value and emotional engagement. Trade articles sometimes look at them through the lens of brain narrative alignment, but much less using the psychology of emotion, mental models, and information processing. Psychology adds a valuable layer over (not instead of) the innovative and creative content) to make sure that ads don’t inadvertently work at cross purposes to the goal. (Do you remember the Chevy Nova? It didn’t sell well in Spanish-speaking countries porque no va.) Understanding the perspective of your audience (or partner, team, boss, friend or children) will make you a better communicator and strengthen your relationships. Understanding how the audience constructs the meaning of visual and verbal content ultimately determines if a commercial is a winner.

References

Dale, E. (1969). Cone of experience. In R. V. Wirman & W. C. Meierhenry (Eds.), Educational media: Theory into practice. Charles Merrill. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405847009542259

Erfgen, C., Zenker, S., & Sattler, H. (2015). The vampire effect: When do celebrity endorsers harm brand recall? International Journal of Research in Marketing, 32(2), 155-163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2014.12.002

Herman, D. (2013). Storytelling and the sciences of mind. MIT Press.

Immordino-Yang, M. H. (2016). Emotions, learning, and the brain: Exploring the educational implications of affective neuroscience. W. W. Norton & Company.

Mehrabian, A. (2017). Nonverbal communication. Routledge.

Moraes, M., Gountas, J., Gountas, S., & Sharma, P. (2019). Celebrity influences on consumer decision making: New insights and research directions. Journal of Marketing Management, 35(13-14), 1159-1192. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2019.1632373

Vogel, D. R., Dickson, W., & Lehman, J. A. (2005). Persuasion and the role of visual presentation support: The UM/3M study.

Dr. Pamela Rutledge is available to reporters for comments on the psychological and social impact of media and technology on individuals, society, organizations and brands.

Dr. Pamela Rutledge is available to reporters for comments on the psychological and social impact of media and technology on individuals, society, organizations and brands.